|

The oldest items in the museum are the Renaissance books that established Italy as the cradle of modern fencing. Written by legendary masters of defence – Marozzo, Agrippa, Viggiani, di Grassi, Fabris, Giganti and Capoferro – whose influence on rapier play extended all over Europe, they are lavishly illustrated by woodcuts or copperplate engravings of the highest quality. Important books from other countries also on display include works by St. Didier, Meyer and, above all, Thibault, whose magnificent treatise on the Spanish school of fencing is one of the finest examples of 17th century printing. |

|

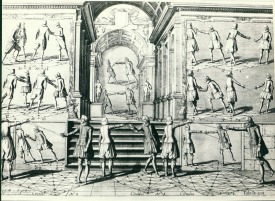

Agrippa, 1553

|

Viggiani, 1575

|

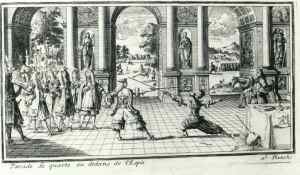

Thibault, 1628

|

In mid-17th century France a fundamental change

occurred in fencing: not only did the civilian sword change from the

rapier to the smallsword, but for the first time a purely sporting weapon

was introduced – the foil – with artificial rules to allow the skills

of swordplay to be demonstrated in relative safety. French masters now

took over the development of fencing. Among them, De La Touche was the

first to illustrate the new sporting weapon and Liancour’s treatise

included some of the most dramatic illustrations in fencing literature,

with backgrounds full of sea battles, towns under siege and castles on

fire. |

|

De La Touche, 1670

|

Liancour, 1686

|

Labat, 1734

|

The museum's oldest foils date from the late 17th

century and all have blades stamped IN SOLINGEN. (The German town of

Solingen, near Dusseldorf, was the major source of foil blades, exporting

its wares to sword cutlers all over Europe.). One has the crown-shaped guard

typical of the earliest French foils. Another, probably Italian, has a

crossbar and ricasso behind an intricate guard of iron loops and a large

leather-covered button that served to protect the eyes during a bout. A fine

pair of early Italian foils with pierced asymmetrical butterfly guards have

a grooved false ricasso encasing that part of the blade between guard and

crossbar. |

Late 17th c. foil, French |

Pair late 17th c. foils, Italian |

Late 17th c. foil, Italian |

The mid-18th century marked the arrival in

England of a man who was to establish one of the great fencing dynasties,

Domenico Angelo. Originally from Livorno in Italy but trained in Paris,

Angelo became the leading fencing master in London with numerous pupils

among the nobility, including George III’s sons the Prince of Wales and

the Duke of York. Their support enabled him to produce the most elegantly

illustrated treatise of the century, L’Ecole des Armes. |

Angelo, 1763 |

|

Two prints capture the flavour of fencing in the 18th

century: James Gillray’s scene of the match between the two most famous

fencers of the day, the Chevalier D’Eon and the Chevalier de

Saint-Georges in 1787 before the Prince of Wales, and Thomas Rowlandson’s

image of Angelo’s Academy in the same year with old Domenico holding a

bunch of foils and watching his son Henry taking part in a bout; both show

the wire mesh mask for the first time, although not worn by the principal

fencers, who considered themselves far too skilful to require such a

safety aid. |

|

D’Eon v Saint-Georges, 1787

|

Angelo’s Academy, 1787

|

| The museum has around 30 foils from the 18th

century characterised by guards with a disc, cup or figure-of-eight

configuration and pommels in the shape of an acorn or, in the last few

decades of the century, an urn. It is unusual to find fencing weapons with

any recorded history, but a pair of foils in the collection can be traced

back to the year 1782 when Henry Howard (1757-1842) of Corby Castle in

Cumbria bought them from the leading English bladesmith, Thomas Gill of

Birmingham, on his return from the Grand Tour. Considerably rarer are

practice small-swords with their triangular blades ending in a button,

which would have been used to prepare for a duel. The museum has just one,

a fine French example dating from around 1765 inscribed Bernard

marchand fourbiseur au Grand Hussar proche La Place d’Armes a Metz. |

|

Case of 18th century foils

|

|

Mid 18th c. German

|

Late 18th c. French |

English, by Thomas Gill

of Birmingham, c. 1782

|

Practice smallsword

French, c. 1765

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|