|

19TH CENTURY |

|

|

Copyright © Malcolm Fare 2005-2025

|

|

|

|

A unique piece of fencing history is a

French fencing master’s diploma or Brevet de Maitre. On the 11th

of August 1811 this was awarded to voltigeur (light infantryman)

Joseph Brault, who had qualified in Dartmoor Prison, the award being made

by 26 masters and fellow prisoners from the 47th Regiment

captured during the Peninsular War. |

|

Brevet de Maitre, 1811

|

|

Among the 100 or so 19th century books in

the museum’s library is an anonymous manuscript entitled The Fencer,

dated 1838, by a pupil of William Angelo; the first works to introduce

epee and sabre to the fencing public; and a bound set of the early years

of the beautifully illustrated fencing magazine, L’Escrime Francaise,

1889-1895.

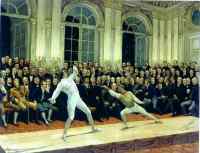

Pictures on show include three original watercolours of

fencers by the prolific French fencing artist Frédéric Régamey, as well

as Régamey’s famous print of the historic match in 1816 between the

Comte de Bondy and the provincial fencing master Justin Lafaugère. There

is a fine coloured mezzotint engraving of a Regency fencer by Francalanza

and a late 19th century watercolour of an impossibly

wasp-waisted French lady foilist by Jean Beraud. Rather more realistic is

the English fencer/artist Frederick Townsend’s watercolour drawing of

two ladies fencing under the watchful eye of their master, Baptiste

Bertrand. An oil painting by Francois Brunery shows Bertrand shortly

before he died in 1898. |

|

Comte de Bondy v

Lafaugere

1816

|

Lady foilists at Salle

Bertrand,1899

|

Baptiste Bertrand

c. 1898

|

|

The second half of the century saw an enormous variety

of fencing weapons appear on the market as a growing interest in the sport

was matched by the technology to produce virtually any style required.

Foils with finely embossed blades mounted in decorative hilts were made

for presentation or were specially commissioned by individual fencers.

A magnificent case of foils dating from the French

Second Empire period is lined with blue velvet and has the Napoleonic

eagle stamped in gold at either end. Probably made for the son of a

marshal, the beautifully decorated blades are just 74.5 cm long. |

|

Case of foils, c. 1860

|

|

One pair of English foils on display has

pineapple-shaped pommels and embossed blades stamped with a king’s head;

their solid brass butterfly shell guards bear the inscription A J

Richards, Radley College, 1862. The blades are among the first to be

stamped with the number 4 which, together with No. 5, began to appear on

foils from the mid-19th century. Why these numbers were chosen

and who began the practice is now lost in the mists of time.

Other foils on display have guards decorated with

acanthus leaves, anchors, military trophies, skull and crossbones,

geometric patterns and even winged cherubs entwined with serpents; pommels

include those in the form of a knight’s helm, plumed helmet, hooded

skull and female head with feathered headdress. |

|

19th c. foil hilts

|

German, c. 1840

|

French, c. 1850 |

French, c. 1860 |

English, presented to A J

Richards, Radley College, 1862 |

English, c. 1870 |

French, c. 1870 |

French, c. 1880 |

French, c. 1880 |

English, c. 1880 |

English, presented

to W J Bourn, 1887 |

Blade etched by Souzy, Paris, c. 1880 |

Blade blued and gilded by Wilkinson, Pall Mall, c. 1890 |

Decorative blade from Solingen, c. 1890 |

Elstree School prize from Angelo’s School of Arms, 1892 |

|

The last quarter of the 19th century saw the introduction of

epee and sabre as fencing weapons. The épée de salle was exactly

the same as its sharp counterpart except for the addition of a buttoned

tip and the museum has several early examples with comparatively small

steel cup guards. One ingenious design, well ahead of its time when

advertised in 1894, incorporates a square pin under the guard, which

secures the blade and can be easily unscrewed to allow a new blade to be

fitted. As well as heavy army practice swords and an example of the first

light fencing sabre, pairs of decorative French duelling epees and Italian

duelling sabres are on display. |

French epee,

c. 1870 |

French duelling

rapiers, c. 1890 |

French epee,

c. 1890 |

French school

prize, 1891 |

French patented epee,

c. 1894 |

Italian sporting sabre,

c. 1875 |

Italian duelling sabres,

c. 1890 |

|

The evolution of the mask can be seen from a simple face cover, followed

by the addition of ear and forehead protectors and a rudimentary bib, to

the full foil mask with leather bib or throat protector introduced in the

late 19th century. Unusual examples on display include a mid-19th

century Cossack sabre model with an extraordinary steel basket head

protector, a singlestick mask made of wickerwork and a beautifully

designed turn-of-the-century Italian sabre mask. |

French, late 18th c.

|

Russian, c. 1850

|

French, c. 1870

|

Italian, c. 1900

|

|

At the end of the 19th century bronze and spelter figures became

popular, particularly in France, and the museum has a few examples of

fencers and duellists in characteristic poses. |

Foilists in evening dress

|

Pupil and master

|

Epeeists by Raphanel

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|